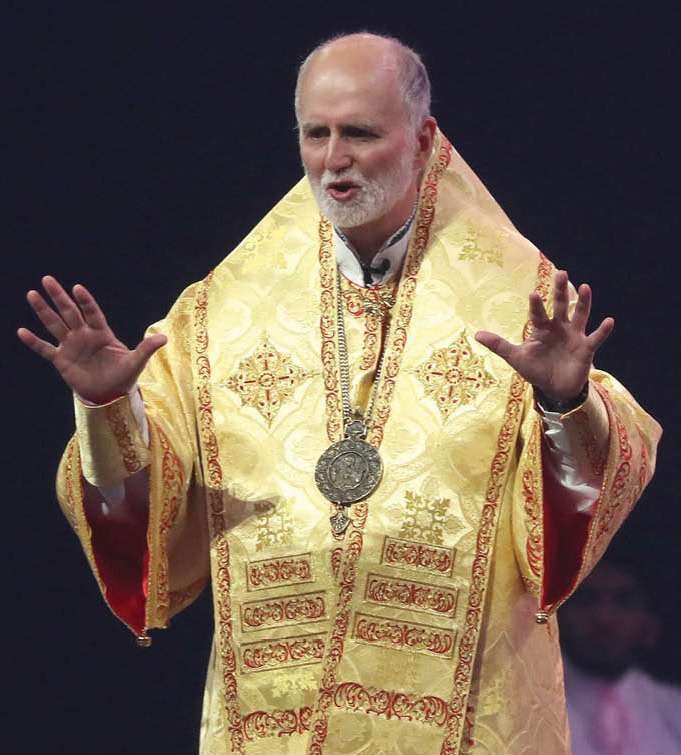

Archbishop Borys A. Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia. (Bob Roller / OSV News / 2024)

By Gina Christian

OSV News

As part of swift and sweeping changes to immigration policy, the Trump administration is aiming to end or severely curtail two forms of immigration status that have been granted to hundreds of thousands escaping war, disaster, violence and humanitarian crises — Temporary Protected Status and humanitarian parole.

Both offer time-bound protection from deportation. TPS — which is granted to those from Homeland Security-designated countries experiencing ongoing crises — typically provides work authorization. Humanitarian parole, in contrast, is generally conferred on a case-by-case basis and, unlike TPS, does not guarantee work authorization.

A Jan. 20 executive order by President Donald Trump ended all categorical humanitarian parole programs, including those for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans, who face humanitarian emergencies, repression, violence and political instability.

“They traveled (to the United States) relying on a promise by our government that they would be protected if they followed the rules,” J. Kevin Appleby, senior fellow for policy and communications at the Center for Migration Studies of New York, told OSV News. “And now the Trump administration has changed those rules.”

“Certainly with humanitarian parole, where we invited these immigrants to come in legally and they’re essentially legal, we’re pulling the rug out from under them,” said Appleby, who served as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ director of migration policy and public affairs from 1998-2016.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed the difficult conditions faced by Cubans when he announced the restoration of a “tough U.S.-Cuba policy” Jan. 31, noting that Cuba remains on the State Department’s state sponsors of terrorism list.

Rubio said the regime provides “food, housing, and medical care to foreign murderers, bombmakers, and hijackers,” while Cubans — who are subject to oppression and surveillance — “go hungry and lack access to basic medicine.”

With the official Feb. 1 termination of the TPS designation for Venezuela, some 348,000 Venezuelans in the U.S. now face deportation back to the South American nation. Their protections end April 7.

Appleby said the TPS and parole pullbacks “violate every tenet of democracy that we’ve developed over the years.”

But Andrew R. Arthur, a resident fellow in law and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, disagreed, telling OSV News that the programs themselves were an overreach of the executive branch.

“Only Congress has the authority to allow people to move to the United States or to resettle to the United States,” said Arthur. “Parole itself is a very limited authority, not a categorical authority. And it was abused in this particular instance.”

“If these are good programs, (and) these are needy and deserving people, the only way you’re actually going to get Congress to act now is to create an ending date for these programs,” he said. Otherwise, he continued, “nothing would be done with respect to their (parolees) status at all.”

Arthur, who is Catholic, added, “I trust Congress to do the right thing. I hope the (U.S. Catholic) bishops do too.”

He also clarified that “the authority that Congress gave” regarding parole is directed to the homeland security secretary. He said that while “there are restrictions with respect to granting parole,” there are “no restrictions whatsoever with respect to ending it.”

Yet in the case of the humanitarian parole program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans — also known as the CHNV program — “these are all nations … that are failed states,” said Appleby. “It’s basically sending people who have a justified asylum claim back to their persecutors and to possible harm.”

Appleby said that efforts to eliminate the key immigration protections failed to “take into account human rights or the lives of people,” and showed “no empathy for their situation.”

Trump’s Jan. 20 executive order also paused the Uniting for Ukraine program, or U4U, launched in April 2022 to grant humanitarian parole to qualified, vetted Ukrainians escaping Russia’s full-scale invasion.

U4U beneficiaries were sponsored by private U.S. residents who financially supported them for the duration of their parole period. As of March 2024, more than 187,000 Ukrainians arrived in the U.S. through the U4U program, with a separate 350,000 welcomed mostly through temporary visas.

The Biden administration had also designated Ukraine for TPS, and had extended that status on Jan. 15 through Oct. 19, 2026.

During a Feb. 4 online press call with several U4U sponsors, Metropolitan Archbishop Borys A. Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia said that while 2 million Ukrainian migrants globally have returned to their nation since Russia’s February 2022 invasion, “there are millions and millions who have nowhere to go” despite wanting to repatriate.

“Their towns have been razed, their cities are under occupation,” said Archbishop Gudziak, who also serves as chair of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development.

Along with numerous faith communities, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church “has been extinguished everywhere there is Russian occupation,” he said, adding Catholic priests and faithful have been “abducted, tortured and killed.”

During the press call, Archbishop Gudziak and participating U4U sponsors said the program was highly efficient and cost-effective, with Ukrainian immigrants bolstering local workforces and volunteering to aid their adoptive communities.

“This is love and service and generosity pouring forth,” the archbishop said. “This is the best of America.”