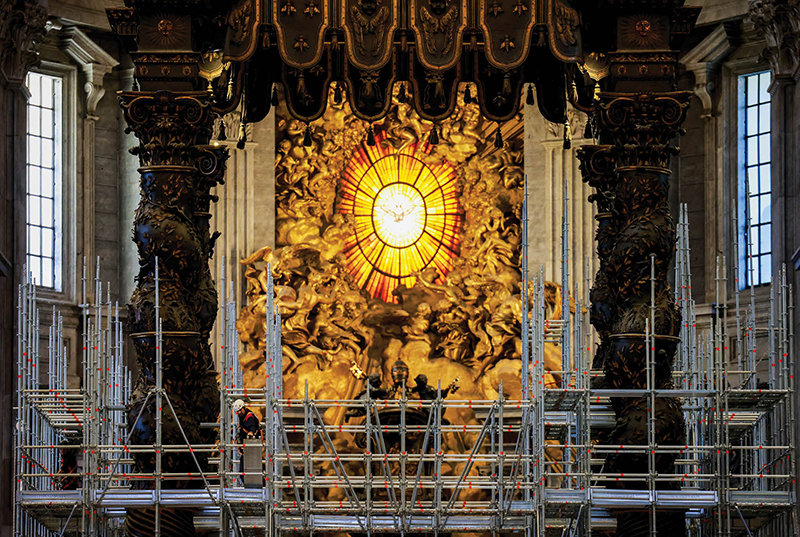

A worker is dwarfed by the 100-foot-tall baldachin by Gian Lorenzo Bernini over the main altar of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican as scaffolding is set up around the bronze canopy. The intricate and extensively detailed sculpture is set to undergo a major restoration. (OSV News / Yara Nardi, Reuters)

By Carol Glatz

Catholic News Service

VATICAN CITY — Like a giant Tinkertoy construction, a skeletal tower of scaffolding slowly inched its way up the twisting bronze columns of the baldachin over the main altar of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Workers on the ground picked through piles of shiny metal platforms, poles, clamps and couplers to then hoist them up high with pulleys to their workmates above. They had begun erecting the scaffolding after Mass on Ash Wednesday Feb. 14 and it reached almost halfway by Feb. 21.

The 100-foot-tall baldachin was set to be completely covered by metal scaffolding before Easter to allow a team of 10 to 12 restorers to start cleaning, repairing and revitalizing the masterpiece designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1624 and completed around 1633.

The biggest problem facing the restorers “is getting there, that is, to be close enough” to the bronze and wood structures and many decorative details that need to be restored, Alberto Capitanucci told Catholic News Service.

Capitanucci, the head engineer of the Fabbrica di San Pietro — the office responsible for upkeep of the basilica — said the baldachin is a monumental architectural structure that is as high as a 10-story building.

But it is mostly empty space with its four fluted spiral bronze columns, each set upon a massive marble pedestal alongside the marble steps leading to the main altar over the tomb of St. Peter. The most delicate part of the structure is the canopy above, he said, which is made entirely of wood.

The wooden ceiling “is the size of a vessel, that is, it was designed to be the wooden planking of a boat,” Capitanucci said.

Despite its enormous size, Bernini wanted the baldachin to resemble the light, open and airy cloth-covered canopy used in processions of the Blessed Sacrament.

The term “baldachin” or “baudekin” comes from a special brocade fabric made in Baghdad and traditionally used for processional canopies.

The twisting pattern on the gilded columns makes them look lighter and draws the eye upward along decorations of snaking branches of olive and laurel, bees and lizards, until it reaches the top which resembles canopy brocade and tassels blowing in the wind, he said. The top of the baldachin is meant to look like “a billowing sail” of a boat.

The angels holding floral garlands and standing at the four corners are 13 feet high, he said, and four scroll-like ornaments, shaped like dolphin backs, go from the corners up to a globe that supports a cross, which is 40 feet tall. There are four pairs of cherubs holding up the keys of St. Peter, a papal tiara and the sword and book of St. Paul.

What looks small from below is, in reality, enormous in size, Capitanucci said, indicating that the bees on top are as long as a briefcase. Pope Urban VIII, who hired Bernini to design the baldachin, belonged to the Barberini family, whose coat of arms consists of three bees.

Capitanucci said drones were used to take over 6,000 photographs of the hard-to-reach canopy and its inner ceiling featuring the dove of the Holy Spirit surrounded by golden fire. The up-close images will help the restorers plan how to proceed with the massive project, he said.

The entire structure will be covered in sheer cloth to shield workers from the public, he said, while still letting in natural light.

And, once the scaffolding is completely up, the wooden box now protecting the main altar will be removed so the altar can still be used for papal ceremonies for the rest of the year. The entire restoration should be completed by the end of December for the start of the Holy Year.

A small cherub swinging from a decorative branch is among the many touches on one of the four bronze columns of the baldachin over the main altar of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. (CNS photo / Fabbrica di San Pietro)

Franciscan Father Enzo Fortunato, director of communication for St. Peter’s Basilica, told CNS the baldachin “is the linchpin of the basilica.”

It draws attention to the main altar, which is “the heart, where the Eucharistic sacrifice takes place, the Eucharistic celebration that is the source and summit of Christian life,” he said.

The current restoration project, funded by the Knights of Columbus, marks only the second restoration since the baldachin was built, he said, the last restoration being in the late 1700s.

When works of art are preserved well, he said, it keeps alive the belief that “beauty leads to God” and it reminds people “what human genius can create.”

The baldachin also symbolizes that it is possible for all people to work together to create something spectacular, Father Fortunato said. Many other artists worked with Bernini to build the masterpiece, including his fiercest rival, Francesco Borromini.

“This makes us understand that teamwork, working together, always bears beautiful and good fruit,” the Franciscan friar said.