OUR GLOBAL FAMILY

Many have commented on how unfortunate it was that it took the murder of George Floyd and the callous deadly harassment of other Black men to bring about an acknowledgment of deep injustices faced by African Americans.

Potentially, there is a greater tragedy: that what we have witnessed may not move us beyond momentary laments, denouncements on social media, donations and some dialogues. This worry derives from the lack of meaningful progress over the past 50 years.

In fact, we now face deep polarization, dehumanizing inequalities and the institutionalization of corroborating policies despite confronting horrific incidents and consistent statistics of sustained and rampant injustice. During this administration, we not only failed to make progress; we reversed gains which were lifelines to vulnerable communities.

Change must begin with a heavy dose of humility that opens our hearts to not only the lopsided realities of the lives of African Americans but also to our own consent, which enables these to persist through time.

It may be hard but necessary to thoughtfully consider Father Bryan Massingale’s point that racism persists because it benefits white people. We may have never uttered a racial slur or acted unkindly but, as Ibram X. Kendi contends, we are racists if we left it alone.

The American church has acted from both sides of the issue, providing aid to those left behind by the system while through silence or calculated trade-offs simultaneously giving a pass to policies and institutions that keep racism in its place.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops statements have unequivocally described racism as a sin and a life issue. Pope Benedict XVI makes clear in “Caritas in Veritate” that charity, the love we have for each other born out of God’s gratuitous love for us, is not only personal in nature but embedded in institutional, political and economic structures.

Yet, discourses by some Catholic media have pitted pro-life against pro-poor in the public square. Some demonize one position over the other with rhetoric that is mean-spirited and demeaning. Somehow the focus on the poor became equated with the lack of concern for life.

Seldom are these pernicious and anti-Gospel rants censured. What is the loss to society, the church’s teaching authority, her potential impact and our individual faith when we failed to insist on the primacy of both issues and capitulated to the “necessary” trade-off?

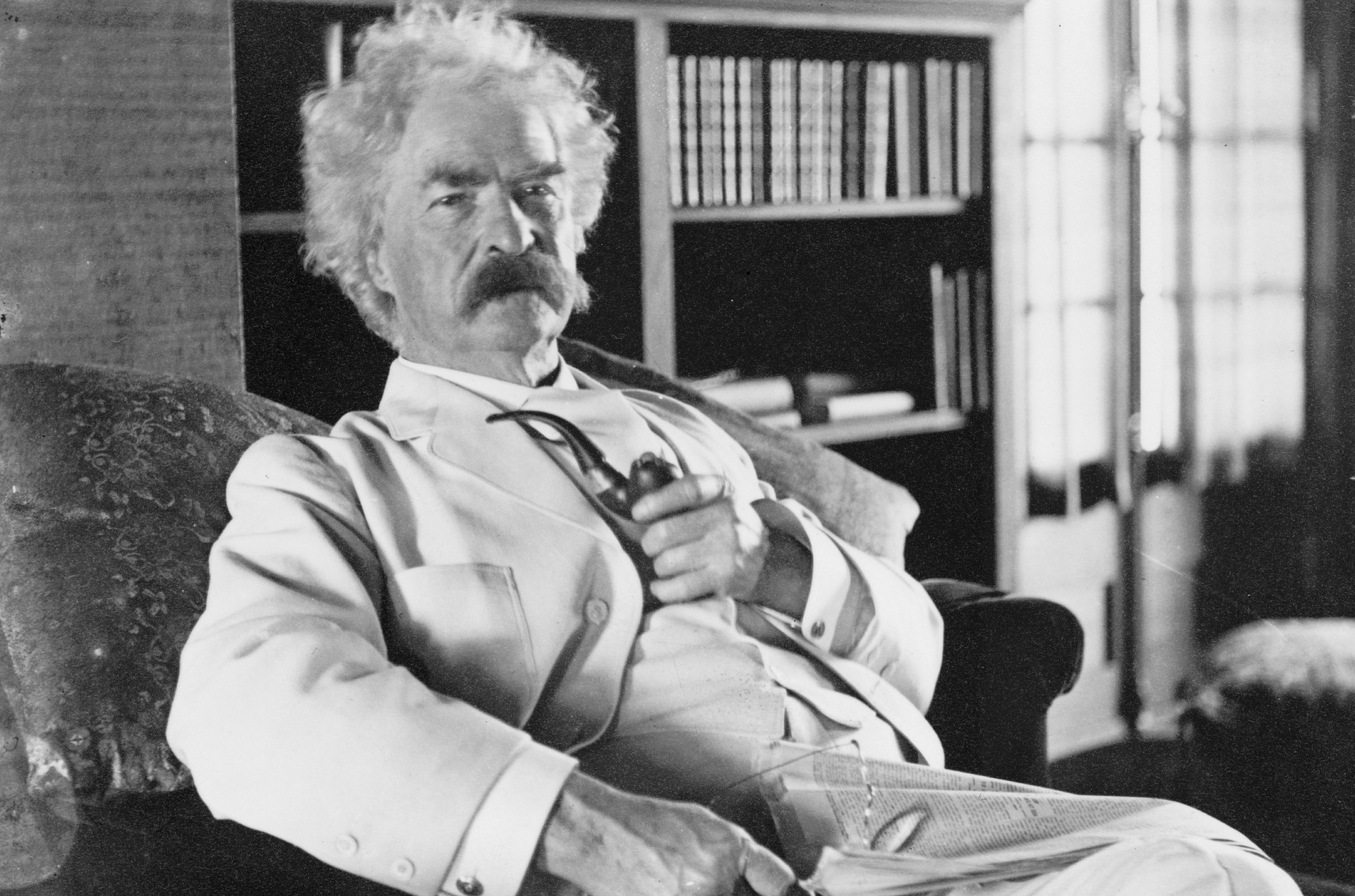

Statements do not by themselves become voice. Mark Twain, wary about religion’s potential corrupting influence, wrote of its influence on his own understanding of slavery:

“In my schoolboy days, I had no aversion to slavery. I was not aware that there was anything wrong about it. No one arraigned it in my hearing; the local papers said nothing against it; the local pulpit taught us that God approved it, that it was a holy thing, and that the doubter need only look in the Bible if he wished to settle his mind — and then the texts were read aloud to us to make the matter sure.”

Chattel slavery of which Twain spoke may be outlawed, but life-defeating racism is not.

Will the present shock be like seeds that fall on rocky ground? Or will they be nurtured in fertile soil? Having been at the foot of the cross of another man crucified through asphyxiation and calling for his mother, what are we to do?

This is not just a moral question, but the journey of the soul after an encounter with Our Lord in the suffering of the other. Jesus told us that new wine will explode the old wine skins. What do we need to do to accept new wine?

Woo is retired CEO and president of Catholic Relief Services, where she served from 2012 to 2016.