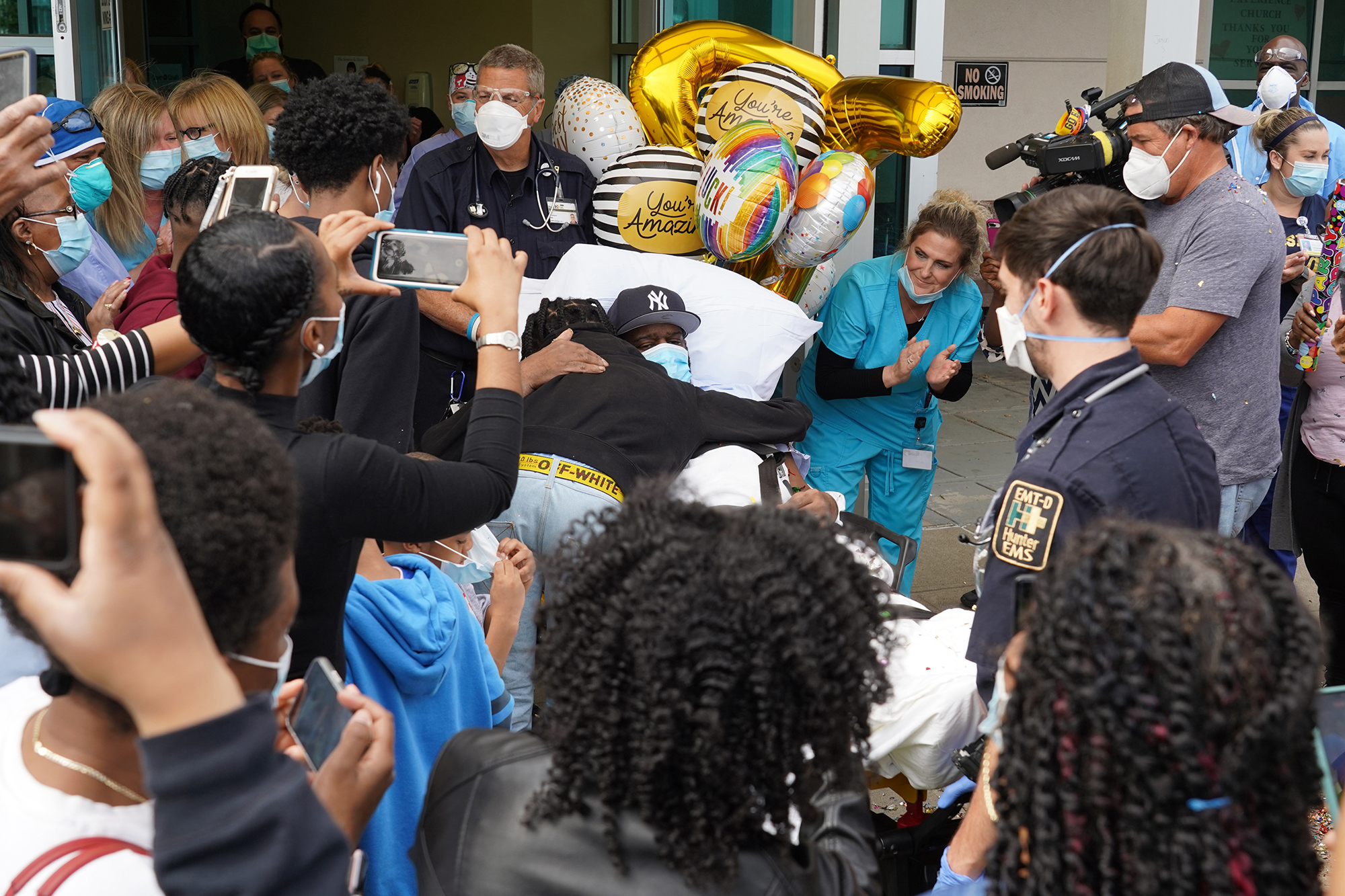

Jerome Smith is hugged by his 19-year-old son, Jerome IV, as he is discharged from St. Joseph Hospital in Bethpage, N.Y., June 2, 2020. Smith, 44, who was to be transported by ambulance to a rehabilitation facility, had been hospitalized for 74 days while recovering from complications related to the coronavirus. Married with six children, Smith is believed to have contracted the virus while employed as an essential worker with the New York City Department of Sanitation. (CNS photo/Gregory A. Shemitz)

FINDING GOD IN ALL THINGS

One of my daily rituals during the pandemic has been to take a walk in my neighborhood. It’s a chance to step away from the news, to cultivate some quiet and introspection, and to pay more sustained attention to people and place.

At this point, I’ve come to think of the neighborhood as a makeshift art gallery. Homemade signs hang in windows with phrases like, “We’ll get through this together,” encouraging passersby. Messages on storefronts and even on the streets themselves — written by children with bright and arresting chalk — express gratitude for those we now know to be essential workers.

I confess that the term “essential employee” used to make me chuckle. Organizations I’ve worked for used the descriptor when inclement weather struck. “Only essential employees need to report for work,” they’d broadcast. Snow days felt like a winnowing of the wheat and chaff: They were when you learned how extraneous you’d been to the enterprise in the first place.

More seriously, the coronavirus has helped to identify many of our society’s unsung heroes, those who humbly report for duty at unglamorous jobs so that others can live in comfort, safety and freedom.

Our health care workers have been chief among those who have been recognized. Their sacrifices have been many: risking their own health, separating themselves from their families while on duty, working lengthy and backbreaking shifts — all without sufficient equipment or knowledge about the virus.

Others getting their due include those in public safety, civil servants, teachers and priests, especially those risking themselves to anoint the sick and dying.

This experience has also drawn attention to laborers who rarely get recognition, namely those who work in low-wage positions. These are the folks who continue to risk exposure to the virus to make ends meet. Their jobs are essential to help people maintain social distancing and keep other sectors of the economy going.

Their contributions are not often done in plain sight, making it easy to take for granted that so many of the services we receive or have come to expect are done by real people with names, families and stories.

As an Axios report pointed out, “Millions of Americans are risking their lives to feed us and bring meals, toiletries and new clothes to our doorsteps — but their pay, benefits and working conditions do not reflect the dangers they face at work.” And at this point, many companies that temporarily raised wages to compensate for hazardous conditions have begun to reverse course.

All of this has me thinking about a passage from “The Long Loneliness,” the autobiography of one of the greatest champions of workers, Dorothy Day.

When discussing why she named her paper The Catholic Worker, Day said this:

“The Catholic Worker, as the name implied, was directed to the worker, but we used the word in its broadest sense, meaning those who worked with hand or brain, those who did physical, mental, or spiritual work. But we thought primarily of the poor, the dispossessed, the exploited.”

She continued:

“Every one of us who was attracted to the poor had a sense of guilt, of responsibility, a feeling that in some way we were living off the labor of others. … We felt a respect for the poor and destitute as those nearest to God, as those chosen by Christ for his compassion.”

Pope Francis recently established a fund to help workers who have found themselves unemployed by the virus. Catholic News Service reported that the pope wants to protect the dignity of those hit hardest by the effects of the pandemic, especially “day laborers and transient workers, those with contracts that have not been renewed, those paid by the hour, interns, domestic workers, small-business owners (and) self-employed workers.”

This is a moment for Catholics to engage in an examination of conscience focused on those whose labor we live off of — to consider how we treat them, whether or not we know them and how we can work to improve their conditions and opportunities, especially during this time of great uncertainty and disruption. That is essential work in which we all can undertake.

Elise Italiano Ureneck is a communications consultant and is a columnist for Catholic News Service.