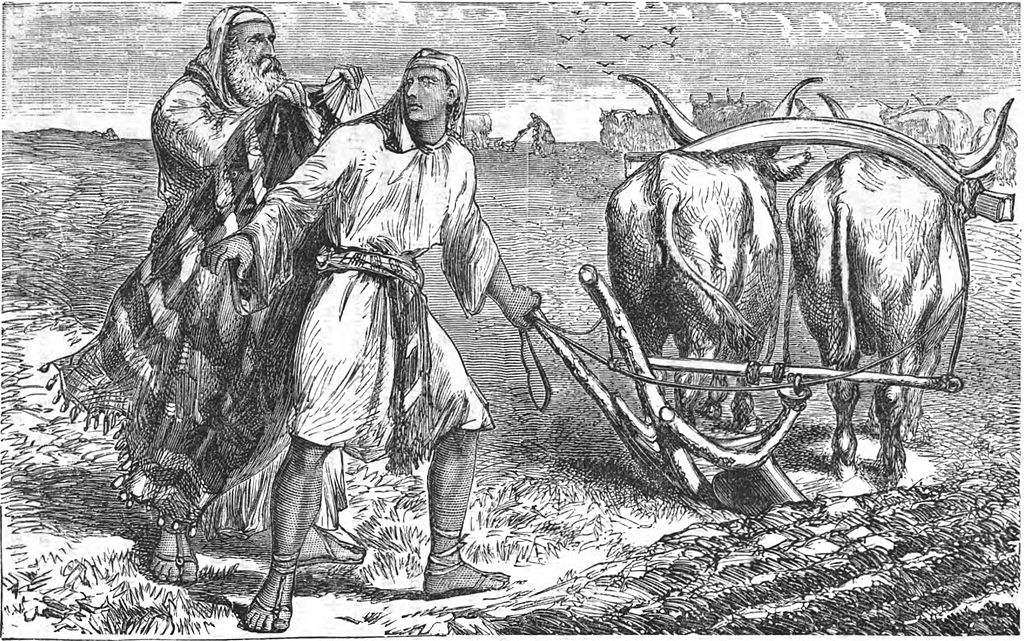

Elijah throwing his mantle on Elisha from an 1873 print in “The story of the Bible from Genesis to Revelation”

13TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME

1 Kings 19:16b, 19-21; Galatians 5:1, 13-18; Luke 9:51-62

The first reading for this weekend’s liturgy is from the First Book of Kings. While the focus, at least in terms of the books’ titles, is on the kings of Israel, prophets play a major role. Such is the case in this weekend’s reading. The king is not mentioned in this selection. Rather, the chief figures are the prophets Elijah and Elisha.

As the Hebrew people gradually were formed into the nation of Israel, and as Moses and his lieutenants passed from the scene in the natural course of events, figures emerged to summon people to religious fidelity.

They were the men whom generations of Jews and then Christians have called the prophets. The English definition of “prophet” is too narrow. Most often, English-speaking persons associate prophecy with predicting the future.

The broader definition, which fits the roles of these Old Testament prophets, was that they spoke for God, proclaimed God’s law, and called the people to religious devotion.

Although the prophets, at least those of whom we have records, and we have records of only a few, often faced rebuke and even outright hostility from the Hebrew people, as a class they were admired.

In this reading the prophet Elijah calls Elisha to follow, and to succeed, him in the prophetic mission. Elisha followed Elijah, forsaking everything else.

For the second reading, the church presents a passage from the Epistle to the Galatians. The theme of this reading is freedom. It expresses Paul’s, as well as the classic Christian, understanding of freedom.

Popular conversation would suggest that persons who are truly free live lives of utter abandon. The more outrageous and extreme the departure from standards, the greater the freedom.

Christian wisdom has another opinion. Yielding to instincts and feelings without question is not a sign of freedom but of slavery. The person who has the perception to see the outcome of certain behavior, and the strength to subordinate actions to an accepted goal, seen as a higher motive, is the person who is free.

St. Luke’s Gospel supplies the last reading. Even today the route from Galilee to Jerusalem passes through Samaria. (Much of Samaria is included in that contested part of the region mentioned today in news reports as the West Bank.)

At the time of Jesus, pious Jews universally despised Samaritans. Centuries before Christ, when many Jews had died during repeated conquests of their land rather than tolerate the conquerors’ paganism, many in Samaria not only had tolerated the conquerors and their paganism, but they had intermarried with the foreigners.

Inter-marriage was a supreme outrage. The Samaritans had defiled the pure ethnic line of the Chosen People by bringing alien blood into their midst.

Jesus spoke with Samaritans, a gesture that caused many Jewish eyebrows to lift. Hearing the disciples’ complaints, Jesus reminded them that the kingdom was not of this world. In God’s kingdom, ethnicity and settling old scores mean nothing.

Reflection

The message this weekend is about the plan of God to give eternal life to all people, who sincerely seek this life, through Christ. First Kings sets the stage. From the oldest periods of history, God reached out to people through the prophets.

References to freedom and to scorn for others come together as advice for us now but also for humans in any age.

We must liberate ourselves from the fears and angers that can overtake us. No Christian can hold anyone in contempt because of accidentals such as race or even earnestly held belief.

The kingdom of God is not of this world. It has its clear realities and demands. Are we free enough to see them and respond to them? Or, are we entrapped in our preconceptions, animosities, personal insecurities and nearsightedness?